I haven't usually had the time to submit to magazines but last year, I was invited to do so. My thanks to Brenda from the Grand River Bead Society who made the recommendation to A Needle Pulling Thread magazine, a beautiful publication which encompasses many fiber arts. My article came out in the Fall 2014 issue but I was not able to reprint it until now.

I was born and spent much of my childhood on a tropical island called Pulau Pinang (Penang) in West Malaysia. The eyebrows of currently snowbound readers are probably shooting upwards as they wonder, "And you left?"

_____________________________________________________________________________

I grew in tropical South East Asia and assumed as a child that everyone was creative. It wasn’t until I was an adult that I realized the women who most influenced my formative years – my maternal grandmother and mother – were extraordinarily talented.

|

| Beaded shoes made by my mother |

My family belonged to an unusual fusion cultural population known as the “Peranakan” (“descendants” in the Malay language) or Straits Chinese. We are the descendants of Chinese immigrants who settled in Indonesia and the Malay Peninsula area (now known as West Malaysia and Singapore) probably from about the late 15th to the 19th century. Few women were among those early settlers so a number of the men married local Malay women.

|

| Beaded bag by my mother |

The male Peranakan became known as Chinese babas and the women, nonyas or nyonyas. The blending of the founding families led to an extraordinary intermixing of language, customs, cuisines, fashion, architecture, jewelry, home décor to a harmonized style uniquely their own. Later on, the Peranakan were also influenced by the British who colonized that part of the world until 1957. Indeed the patois spoken at home was a mix of Chinese, English and Malay.

|

| My maternal grandparents in 1948 : Grandmother shown in her nonya kebaya |

|

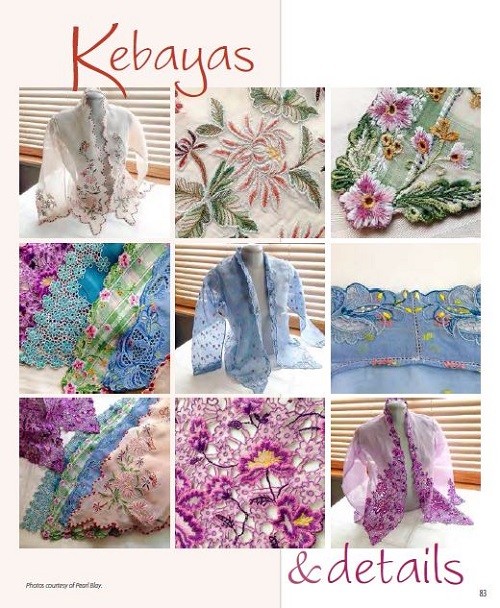

| Embroidered Nonya Kebayas |

Before then, the nonya wore simple dark brown cotton print blouses called baju panjang (long dress in Malay) adorned with a set of triple brooches (kerosang) with top knot hairdos to match. But these gave way to starched kebayas made of transparent material, typically voile, of different hues, adorned with intricate machine embroidery.

|

| Grandmother in her baju panjang and wearing kerosang jewelry c.1930's |

The kerosang also went from the one large and 2 small sets called ibu anak (mother child) to 3 identical brooches chained together. The triple brooches became “buttons” as the kebayas had no closures. Check out this fantastic blog post by Melsong where the author and friends got to dress up in authentic nonya clothes and gorgeous jewelry for a heritage celebration.

|

| Cutwork embroidery of my grandmother's nonya kebaya |

All she had was her single stitch treadle machine. Yet she was able to create amazing patterns with just running and satin stitches. The satin stitches were made by moving the hoop to and fro. To create texture, she would add layers of different colored threads. She often used the cutwork embroidery technique. My grandmother once delighted me with the story of how my mother at age 3 ruined a client kebaya when she climbed up onto the sewing machine and used the embroidery scissors to make holes in the fabric just like my grandmother!

Joining the pieces was also beautifully done with a cutwork stitch called ketuk lubang (“forging holes”). The tiny perforations along the seam lines are so delicately even! Many of my grandmother’s kebayas were given to me after she passed away and are now treasured heirlooms.

Growing up, Grandmother had to learn to embroider and do bead work. These were considered necessary skills for young women in her day. Nonya brides were expected to give their new in-laws beaded items like spectacle cases, purses, shoe vamps, pillow or bolster ends, decorative panels and so on.

Indeed, nonya women practically bead embroidered everything in sight. Anything from curtain tie backs to even the pouch that held the marriage certificate as shown in this example which I photographed at the Peranakan Museum in Singapore :

Like many nonya brides, Grandmother embroidered her own wedding slippers called kasut seret (literally translated as “shoe drag”) using a fabric base and metallic threads. But the kasut seret went out of style not long after she got married in 1930.

The kasut manek (“shoe bead”) became much more popular. Fashionable nonyas would make new pairs to match new outfits. The typical shape of both the kasut seret and kasut manek was a rounded closed toe style but open toed and pointed toed versions also came into being.

The beadwork featured 19th century Chinese motifs but gradually western influences crept into the designs. For example, where peonies once dominated, roses now prevailed. Even geometric patterns were included.

The most common bead work technique was the one in which each bead was sewn down on a piece of fabric which had been stretched on a frame. A grid was drawn on the fabric to aid bead placement. Shoe vamps were always worked on in pairs to ensure the pattern remained correct especially if one side was the mirror image of the other.

This kind of bead work almost died out but has, like the nonya kebaya, seen a revival in recent years. My own mother began to make beaded shoes, bags and pictures after she retired as a teacher. She bought up vintage nonya beads as much as she could! But had to admit using some of the tiny beads from the past was impossible because no one made needles small enough to go through them anymore! Today she uses Japanese seed beads. Instead of having to draw out the grid, she uses appropriately sized aida cloth.

My mother was lucky as there were still artisanal shoemakers around who could give her the vamp templates so she could make vamps for more modern shoe styles. Shown above are shoes, bags and a picture she made for me. Unlike my grandmother, my mother does not sell her work but enjoys the creative process immensely to the delight of many family members who are privileged to receive those gifts.

References

The Nyonya Kebaya: A Century of Straits Chinese Costume

The Peranakan Chinese Home: Art and Culture in Daily Life

Before You Go:

Original Post by THE BEADING GEM

Jewelry Making Tips - Jewelry Business Tips

Joining the pieces was also beautifully done with a cutwork stitch called ketuk lubang (“forging holes”). The tiny perforations along the seam lines are so delicately even! Many of my grandmother’s kebayas were given to me after she passed away and are now treasured heirlooms.

|

| Ketuk Lubang : perforated seam embroidery |

|

| My grandparents on their wedding day c. 1930 |

Like many nonya brides, Grandmother embroidered her own wedding slippers called kasut seret (literally translated as “shoe drag”) using a fabric base and metallic threads. But the kasut seret went out of style not long after she got married in 1930.

|

| Grandmother's wedding slippers |

The kasut manek (“shoe bead”) became much more popular. Fashionable nonyas would make new pairs to match new outfits. The typical shape of both the kasut seret and kasut manek was a rounded closed toe style but open toed and pointed toed versions also came into being.

The beadwork featured 19th century Chinese motifs but gradually western influences crept into the designs. For example, where peonies once dominated, roses now prevailed. Even geometric patterns were included.

The most common bead work technique was the one in which each bead was sewn down on a piece of fabric which had been stretched on a frame. A grid was drawn on the fabric to aid bead placement. Shoe vamps were always worked on in pairs to ensure the pattern remained correct especially if one side was the mirror image of the other.

|

| My mother's completed beaded shoe vamps |

This kind of bead work almost died out but has, like the nonya kebaya, seen a revival in recent years. My own mother began to make beaded shoes, bags and pictures after she retired as a teacher. She bought up vintage nonya beads as much as she could! But had to admit using some of the tiny beads from the past was impossible because no one made needles small enough to go through them anymore! Today she uses Japanese seed beads. Instead of having to draw out the grid, she uses appropriately sized aida cloth.

My mother was lucky as there were still artisanal shoemakers around who could give her the vamp templates so she could make vamps for more modern shoe styles. Shown above are shoes, bags and a picture she made for me. Unlike my grandmother, my mother does not sell her work but enjoys the creative process immensely to the delight of many family members who are privileged to receive those gifts.

References

The Nyonya Kebaya: A Century of Straits Chinese Costume

The Peranakan Chinese Home: Art and Culture in Daily Life

Before You Go:

- Malaysian Bead Work and Traditional Costumes

- How Bali Silver Beads are Made

- 4 Ways to Create Surface Bead Embroidery

Original Post by THE BEADING GEM

Jewelry Making Tips - Jewelry Business Tips

Thank you Pearl for sharing this most interesting personal history.

ReplyDeleteHow fascinating and inspirational, Pearl! Thank you so much for sharing this and congrats on being featured in such a beautiful publication :)

ReplyDeletePearl,

ReplyDeleteI really appreciate that you shared this. It is a fascinating article and so personal. Your grandmother's and mother's work are exquisite. I learned so much from this.

I am in awe,

Zan

Thank you all for your kind comments! I am so glad you enjoyed reading something personal for a change. I believe our genes, our families and life experiences all contribute to our creativity!

ReplyDeleteThank you for sharing those beautiful works of art. Where did they ever get the time to produce such intricate detail with such tiny beads.

ReplyDeleteWell, they didn't have tv or the internet in those days! And the women could not work outside the home.

ReplyDeleteI enjoyed reading your article very much. Thank you for sharing.

ReplyDeleteThis was totally amazing and I read every word!! I loved it!! Thanks for sharing your personal history, oh and those pictures!! What a treasure:)))) Wow....I love it when you do historical posts anyway, but I never would have known about this kind of beading any other way!

ReplyDeleteYou come from a very talented family my friend. And for me this explains how you came by your wonderful name!

ReplyDeleteI was very intrigued by the vamps! Not a lot of people even know what vamps are and now I think you've helped with that as well.

Wonderful post. Absolutely wonderful Pearl!

Chuckle! Yes, some Oriental families love the precious gems as names - probably because we are precious to them! But I was actually named after the jewel of the month I was born. Glad you enjoyed it!

DeleteSo you have a birthday coming up sooner than later!

DeleteI still love your name. It's unique and really suits you!

I used to think it was too old fashioned. But ever since I started making jewelry, it is a great name to have. People often remark on it when they see or know about my jewelry.

DeleteThanks for sharing, Pearl! What a history you have!

ReplyDeleteIt is a history that I didn't fully appreciate for many years!

DeleteThank you for his wonderful look into your heritage and the gorgeous beadwork! The photos, everything is exquisite!!

ReplyDeleteGrandmother's work is indeed astonishing when viewed close up! It is incredibly taxing to do those tiny satin stitches the way she did. That is why so few people can do it. And some of the beads my mother used in her creations were older beads at around 18/0.

DeleteWow, really interesting article, thank you. And congratulations on having your article published.

ReplyDeleteThis won't be my last publication! I do have another submission in the works. Now you all know that I come by my genes honestly - nonyas LOVE jewelry too!

DeleteHi Pearl, looking at these post, I could relate all the beading and embroidery work with the heritage items at my home. In western India, beading was considered to be one of the must have hobbies for women. My mom has brought many such purses and shoes when she got married as a part of memories from her parents' home. And all those stuff is handcrafted. I still have beaded curtains at my home. And embroidery is still.part of our outfits. Even I have many outfits hand embroidered work on them! :)

ReplyDeleteIndia has such a long and varied history of gemstones, beading and jewelry! All of which is an incredible cultural heritage for you too, Prakruti!

DeleteThank you for sharing your family history. I've been trying to find a way to get in touch with anyone who may have antique cut beads. I would also like to communicate with beadworkers from your culture. I'm an enrolled member of the Crow Indian Tribe of Montana, & I've been beading since I was a small girl (38+year ago). I learned from my grandmother, who also gave me my first antique seed beads. I've been using & collecting them ever since. We Crow Indians, like beadworkers from your culture have also always favored using faceted seed beads. Do you know anyone who may have antique seed beads who would be willing to either sell or trade for them? I have a huge inventory of faceted, true cut, charlotte seed beads.

ReplyDeleteCan you email me? I might know someone who is willing to trade. Alas I don't know any beaders from SE Asia as I moved to Canada decades ago.

Deletebeadinggem@yahoo.ca

Gorrrrjuss, the purple nonya kebaya! I've tried this type of embroidery myself, and my hat goes off to all those who actually can manage it (I could not {sniff}, even tho I've been machine sewing since '67). Thanx for the interesting post! :)

ReplyDeleteCraftyWummun

Just beautiful. Thank you for sharing your heart and heritage.

ReplyDeleteI don't how how I missed reading this post of yours before. I didn't know that you were Malaysian! Earlier this year, I visited KL and had time to visit both the Islamic arts museum and the traditional textiles museum where I saw several items that you have described here. I was particularly taken by the ornate brooches and the belt buckles

ReplyDelete